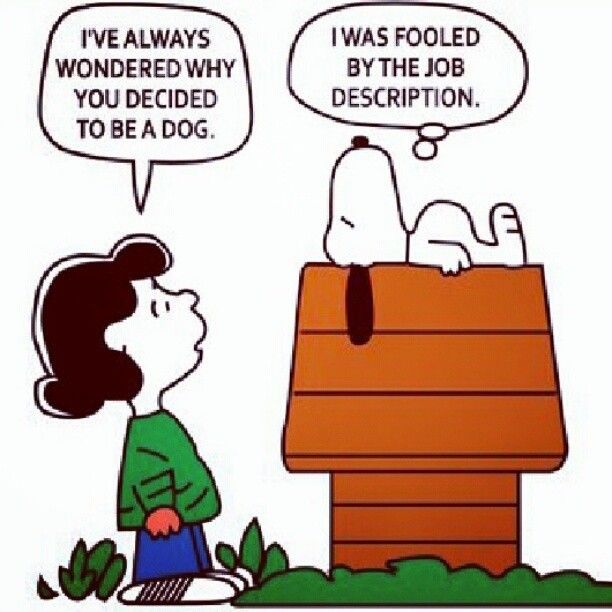

Charles Shultz

It often seems that school leadership is a tight rope strung between the opposing realities of doing a job or living a vocation. There is a big difference between the two, but like many aspects of our roles, the edges are easily blurred.

. . .

Teaching as a whole used to have vocational undertones. In fact, many education jurisdictions had fairly hard-core rules about what teachers could or could not do – even outside of what was considered ‘school time’.

You’ve probably seen the lists floating across the interweb. Lists with things like:

- Men teachers may take one evening each week for courting purposes or two evenings a week if they go to church regularly.

- After ten hours in school, the teachers may spend the remaining time reading the Bible or other good books.

- Women teachers who marry, or engage in unseemly conduct, will be dismissed.

- Every teacher should lay aside a goodly sum of his earnings for his benefit during his declining years so that he will not become a burden on society.

- Any teacher who smokes, uses liquor in any form, frequents pool or public halls, or gets shaved in a barber shop will give a good reason to suspect his worth, intention, integrity and honesty.

- The teacher who performs his labor faithfully and without fault for five years will be given and increase of 25 cents per week in his pay, providing the Board of Education approves.

Some of these demands have probably been exaggerated over time (as happens online), but the under current, the climate of teaching in our historical past, was very controlled with a focus on service at the likely expense of personal freedoms. The historical context made this possible and teachers weren’t alone; nurses, doctors, and other ‘caring’ professions had their own vocational expectations.

But what about now? What about today in your school?

I believe that snippets of this past model are still very much alive. The key difference is that they are implied, rather than written in contracts. The Human Rights Commission would be in for a busy time if they were documented! The problem is that implied expectations are still incredibly real.

. . .

The model of education that we work inside of now, was designed a loooooong time ago, yet many of the basic structures are much as they always were. A lot of arbitrary ‘rules’ are still followed.

For example, in New Zealand, children start formal schooling at 5 years old, they come to an institution Monday to Friday at a set time where there is generally one adult (the teacher) responsible for around 25 – 30 individuals. One person (the principal) is responsible for all aspects of the school’s operation. The curriculum is set by a central Government group and the focus is on creating economically contributing citizens – just like it was well over 100 years ago!

So, if the basic structure of schooling is still very similar, how much sub-conscious expectation still exists that our professional is vocational? Through conversation with other school leaders I’d say there is a lot!

For example, how do you feel about regularly going for a walk at lunchtimes? Or even sitting down and having a lunchtime? When that community fundraiser is on over the weekend, do you put personal plans second as a default? If you are heading home at 4.30pm (potentially having done a huge amount of productive work) do you feel guilty about calling into the supermarket?

And therein lies a daily problem – how do we stay fulfilled, effective, and well in our roles when many of the expectations on us come from a past where working in schools was seen as vocational?

My answer is increasingly to do with being brave. Brave enough to silence those nagging little voices which are based on fear, not reason, and brave enough to work in ways that make me sustainable in a complex and highly demanding role.

Perhaps it helps if we substitute the word ‘brave’ for the word ‘professional’. A professional sets limits, a professional values their own time and energy, a professional works in a way that is sustainable.

And if you need even more convincing, consider for a moment the future school leaders who will take your place. They are already in our schools and they are watching and noticing how we do our jobs. This is an opportunity, in a world of change, to lead by modelling better – better balance and better professionalism.

For many (most?) of us, a vocation is not what we signed on for. We expected to work hard, to be dedicated and committed – to treat our role with the respect deserved, but we didn’t choose to make it the only and defining thing in our lives. We also chose families, hobbies, friends, and health as well.

So, by all means treat your role as a vocation. If that’s what it truly is for you, embrace it and relax into the lifestyle that comes with this choice.

But if it’s not, you need to start bravely resisting the pressure to treat it like it is. Set reasonable limits, prioritise sustainability (yours!) and be an even better leader and role model for the future.

Dave

And as a late breaking piece of news that is very relevant to this discussion, The NZ Government has just announced a 3 year pay freeze on public service pay. Very telling is a statement by our Minister of Education, Chris Hipkins, quoted in the New Zealand Herald –

“We want the public service to use modern, progressive employment practices, and be a great place to work. We also want a productive unified workforce grounded in the spirit of service.”